Research in Fiction Writing: How Fiction Writers Can Balance Imagination and Realism

Alrighty then, my ducklings, time for another tidbit. If you’ve read any of my previous posts for Blue Leaf Editing, you’ll know my name and credentials.

If you haven’t, let’s quickly get introductions out of the way: Shaun’s the name, writing’s the game, and I’ve published several short stories over the years (usually with some historical setting).

I currently have a few stories making the submission rounds and a little project in the works with Blue Leaf Editing (ever wonderful, ever patient).

I’m also a stickler for research in fiction (especially when you’re writing historical romance). It’s one of the reasons why I’m so fond of Georgette Heyer.

She really went the extra mile to reign true to the period she wrote about. That’s what we’ll be covering today: the balancing act between staying true to the setting and making it exciting for the reader.

Table of Contents

Preparing Yourself

I want to make sure you understand a few things before you get into the nitty-gritty details. I’m sure many of you already know what I’m going to say, but I will say it anyway: You’re never going to get all of it right. No, no, Julie—let me explain before you start panicking. If you try to reach perfection, you’ll never be happy with anything you write. There’ll always be one more fact to check, one more description to rewrite.

Ah, I can already hear some of your thoughts: If that’s the case, how do you know that your story is good enough, then? Well, that’s going to come with practice. The more you write, the more you read, the quicker you’ll start to identify when a story is decent. This brings me back to today’s topic: research—why it’s important and why you’ll probably never get it as accurate as you want.

Why Is Book Research Important?

Should You Care About Little Old Facts?

This is something I’ve wanted to talk about for a long time. If you’ve ever read a historical novel, watched a period piece, or got comfy for your weekly episode of Grey’s Anatomy, you know there’s a level of research that needs to go into making the story believable. It must give off a certain scent of authenticity.

Initially, it might not seem important, but wow, do the plot and characters suffer when writers don’t put in the work to paint the setting properly!

Always Enrich, Never Sacrifice

Simply put, we’re all just human: historians, writers, mapmakers—the whole lot. Humans make mistakes. They made mistakes in the 11th century and they make mistakes now. As a writer, your job is to get the facts as close to accurate as possible for your story without boring your readers.

This is where I suggest you follow a simple rule: use research to enrich a story and never sacrifice a story for the sake of research.

What do I mean by that? Jemma? Ah, yes, quite right. Fiction aims to entertain. Some people might disagree with that statement, of course—I see James frowning over there—but this is a personal belief of mine.

Most people buy fiction to escape reality. They want something that pulls them in and makes them feel. Some people want to be scared because they’ve cried too much in their lives; some people want to experience love in a way they might never be able to—but that’s another carton of eggs altogether.

The point I’m trying to make is that research needs to help your story meet those expectations.

Boring Readers When Speaking of Magic

I’m going to be very honest with you—and it pains me to say it!—but sometimes, even Georgette Heyer’s novels get too caught up in the minutia of her research. The story becomes a bit stilted, sacrificing entertainment value for a quick history lesson.

Now, before Heyer fans burn me at the stake for saying it, remember, I’m a Heyer fan as well, and I actually enjoy a few history lessons in my fiction—but I can step back and look at something objectively.

This reminds me of a quote from Susanna Clarke’s magnificent novel, Jonathan Strange and Mr Norrell, in which she says of Mr Norrell: “He hardly ever spoke of magic, and when he did it was like a history lesson and no one could bear to listen to him.”

There’s a lesson in that sentence: avoid information overload.

Don’t bore people with too many irrelevant details when you’re telling a story you’re passionate about. Build your world, place your character in it, and have your readers eager to turn the page.

Accuracy and Allowing the Human Element

Now, people will disagree with this (what else is new? People disagree with everything), but research and imagination can go hand in hand. Let’s look at an example. Who can give me a genre? Chris? Ah, you’re really trying to get into my good graces, aren’t you?

Regency romance. I love the sub-genre. Most of my favourite stories are set during the period.

I love to research it. Looking at the fashions of the period (no, Stacy, Bridgerton’s costumes aren’t entirely historically accurate. Liberties were taken with those, but they are pretty)—where was I?

Ah, yes. Looking at the period’s fashions, you’ll notice that the most prominent examples come from places like La Belle Assemblée and The Lady’s Monthly Museum. Many writers and researchers—especially those who only conduct it superficially—point to these sources and cry: “Look! This is the image, this is the portrayal! Any deviation must be wrong!”

That’s simply not true.

Now, let’s use some of our imagination. I want you all to picture your grandparents. Think about how they dress, how they go about their routines and do their hair. Chances are they have vastly outmoded senses of style, right?

Well, I can’t point to any concrete sources at the moment, but I think it’s safe to assume that every single lady didn’t throw out her 1790s fashions simply because La Belle Assemblée said so.

It’s not the human way—it’s not even the way of fashion, mind you. Change doesn’t happen overnight, across the board.

What does this example teach us about researching for fiction writing? Jemma? Yes, that’s a good one, I’ll write it down

Research for historical fiction should always allow some room for a human element.

Anyone else? Maybe a takeaway that applies to more than one sub-genre? James? Ah, I knew you were going to mention that one.

Know the rules before you break them.

Strutting on the Tightrope While Writing Fiction

Let me tell you a secret: You’re not writing non-fiction. You’ve got to remember that. A reader picking up one of your books should get what they’re expecting: characters, plot, some form of story and setting, and worldbuilding.

We’ve already covered the “always enrich, never sacrifice” bit, but James pointed out another important bit of advice: knowing your rules before you decide to break them.

This is something I feel that most English teachers don’t touch on enough. I’m sure many of you’ve thought: “If I do it, it’s a mistake; but if Hemingway does it, it’s literature!” Why do you think that is?

Yes, it’s because, for all intents and purposes, Hemingway knew what he was doing and what rules he was breaking. Oftentimes, students don’t, and that’s where the difference lies.

When it comes to research in fiction writing, the same mentality applies.

Shaping and Breaking the Mould

When you’re writing, characters only know what you know. You can fool people, of course. None of us know how to do surgery, fly a spaceship, or summon a demon (I’m being rather optimistic about that last one), but we can make people think we do.

To break a rule without having it seem like a mistake, you need to be able to identify the rule you’re breaking. Readers pick up on cases where writers didn’t do the work. Not always, mind you, but more often than you’d think.

Another example—one I think blatant enough for all of us to have an opinion on—would be romance book covers. Yes, I know they’re there to sell the book.

Yes, I know they (apparently) do that job pretty well (despite the prospect of embarrassment at having to read one in public), but have any of you noticed how historically inaccurate those covers usually are?

Good, I see quite a few hands going up. Stacy, what have you noticed about them? Don’t even get me started about the makeup, my dear. Have you seen some of the covers for old Heyer novels? Let me tell you, heavy mascara and the Regency don’t mix half as well as people thought they did.

Anyone else? Jemma? Ah, the fashion! Corsets on bare skin, no chemise in sight? Couldn’t be comfortable.

This is an example of where, in my opinion, rules were broken to the detriment of believability.

Avoid and Disregard Research in Fiction Writing at Your Peril

Not knowing anything about your current work, I can’t provide exact fiction writing research tips. It’s up to personal preference.

(After all, I’ve always really wanted a fantasy fiction book in the vein of Marie Brennan’s Memoirs of Lady Trent, but with writing that reads a bit more like an encyclopaedia. Many people won’t like it, though, for the exact reason I would.)

For the most part, though, I can guess that the story you’re writing is inspired by some of the stories you love. You’re writing a Gothic with your own twist, an epic fantasy set against a backdrop inspired by Earth’s medieval period.

Whatever your story might be, make sure your research doesn’t gobble up your imagination like some ogre under a bridge—but also make sure there’s no ogre at all.

As we’ve just discussed, sometimes breaking the rules—knowingly or unknowingly—can betray a story. There are many books that I, for one, put aside because of several silly mistakes and inaccuracies that would’ve been remarkably easy to fact-check (and not only books, mind you, but movie and television shows as well. Keep your eyes out for the pesky missing chemise conundrum).

Do your research, my dear students. Some of you will feel the need to wing it—especially those of you who are discovery writers—and that’s perfectly fine. It’s going to take some time to sharpen your skills and a lot of comfortability in the world you’re writing in, but it’s doable.

Whatever your preferred method of writing is, understand what can be done, what should be done, and what must be avoided at all costs.

The Importance of Worldbuilding Research in Your Genre

When people talk about worldbuilding, they often talk about it in terms of fantasy.

Worldbuilding is, in fact, used in every single genre: mystery, fantasy, romance.

Most people are worldbuilding without even knowing it—even those writing YA romance. I’m here to tell you—or, rather, politely suggest—that you take that bull by the horns and start actively developing and organising your setting.

This is not to say that you must have every aspect of the world analysed, researched, and down on paper before you even start writing.

The most important part of worldbuilding is understanding what’s possible and plausible in your setting—this is where research is ridiculously important. Imagine you’re writing a contemporary romance set in South Africa and you decide to have your characters narrowly escape a bear attack.

There are no bears in South Africa. A lot of readers will notice and wait for an explanation (the bear could possibly have escaped from a zoo?), but if you don’t realise you’ve broken a rule—in other words, you haven’t done your research—chances are that readers will be pretty ruffled by something like this.

Understand me, my dear wordsmiths: feel comfortable in your fictional worlds before finalising your stories. Notice how I use finalising instead of starting.

By the end of the first draft, you should have a good indication of what you’ve created—the world you’ve built, whether it’s your corner of Regency London or a long-forgotten kingdom beyond our reality.

Tools for Research in Fiction Writing

I’m not going to sit here and say one way of researching is better than another. As you no doubt know, it’s your meadow and your daisies. But here’s my two cents on which tools you can use to help you with your research.

A good old-fashioned pen and notebook works well, but we live in an age of technology. I’ve scoured the internet for a long time to find useful apps for organising research and worldbuilding.

Even if it’s just for little things in my head or scribbles that’ll never see the light of day, it’s good to keep tidbits available if they ever should come in handy with your larger projects.

These are my favourite apps and tools (on different platforms) to get your research neat and ready to be used:

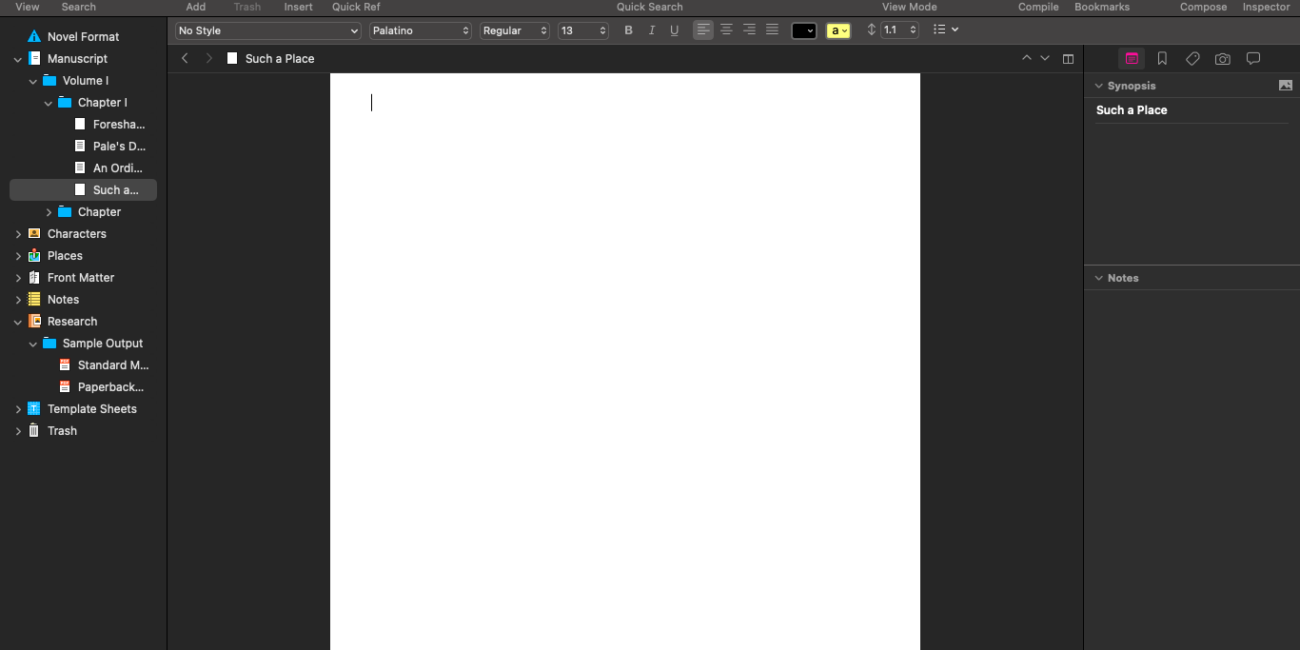

Scrivener

Scrivener, if you don’t already know, is a word-processing software that prides itself on serving individual writers’ needs. Think of it like a digital notebook or binder that you can tweak to your liking. One of my favourite features is opening two files in the same project for a side-by-side comparison—it makes writing historical descriptions much easier.

It’s a learning curve, mind you, but well worth it. I bought Scrivener with the money from my first professional short story sale. Ever since, I haven’t used anything else to write. It’s a tool that I can’t recommend highly enough, but it does have the downside of a hefty price tag.

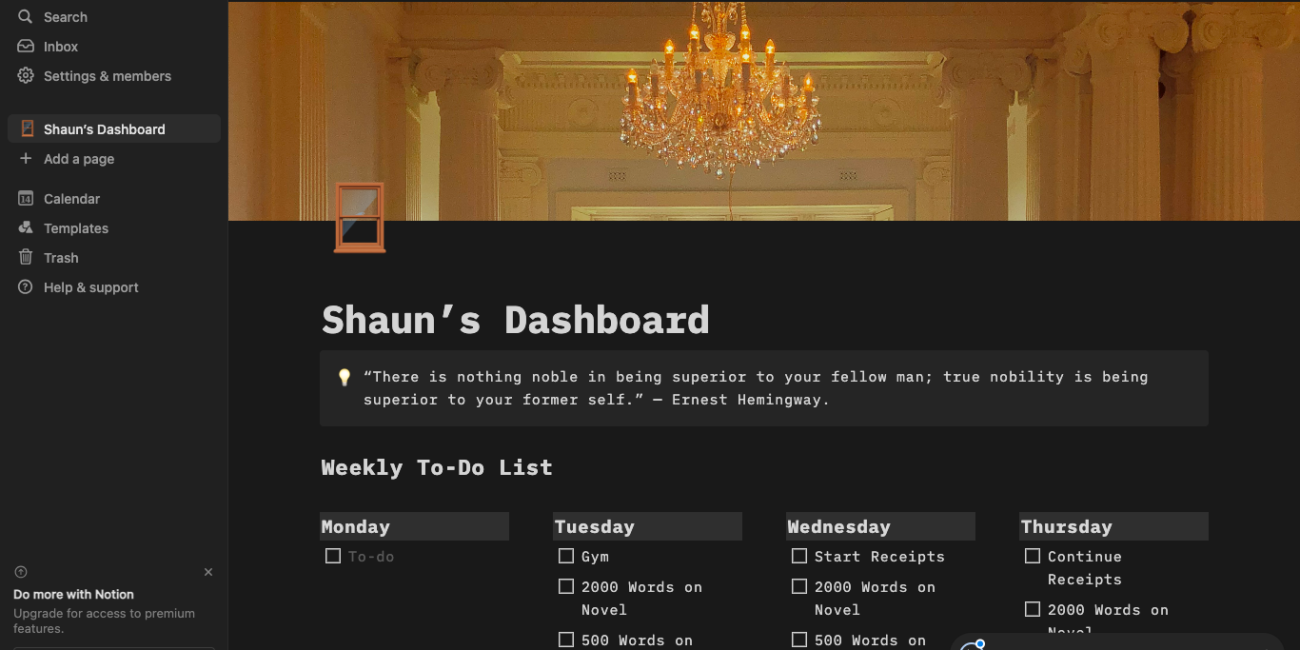

Notion

If you don’t have the funds for Scrivener, the next best thing is Notion. It’s a web-based, all-in-one workplace that synchs across supported devices. It’s free for single users, and its features are legion. It’s beyond customisable, but, like Scrivener, it’s a bit of a learning curve.

I highly recommend it for research and, if you feel so inclined, even writing. There are so many features that’ll benefit you when it comes to organising your thoughts—you can even start your own wiki.

And once you get your Notion set up the way you want it (they have some helpful guides if you get stuck), it’s smooth sailing. Better still, you’ll have quick access to all your information, images, and documents from almost any device.

Novelist

Free and easy to navigate, Novelist is a hidden gem of a word processor available on mobile app stores and PC web browsers.

I dislike working with Microsoft Word on mobile devices, so Novelist comes in handy when you need a place to take effective notes and organise your thoughts by works in progress. It’s basically a free and (very) simplistic version of Scrivener.

Unfortunately, it has a few downsides. For one, it’s not as customisable as either Scrivener or Notion. For another, it still has some bugs that need to be sorted out (specifically on the browser-based version), but it really is a nifty little tool to use on a mobile device if you want to jump right in and get something down quickly.

Homework for Research in Fiction Writing

That’s it, another ready bit of mind food for you to go and digest and do with as you will. For additional reading, I highly recommend visiting Diana Gabaldon’s blog (she has a very smooth way of researching and writing, which I feel would appeal to most discovery writers) and Margaret George’s website (a relatively straightforward approach to research in fiction writing that would most likely appeal to planners). Another great stop, and definitely worth a read, would be Helen Benedict’s article over at The Center for Fiction, Research in Fiction—Necessary But Dangerous.

At any rate, do what you do and explore, read, and learn. We live in a wonderful age where we can find whatever we need, in a multitude of viewpoints, with a simple click of a button or a visit to the library.

That’ll be the homework for today: research the ways of researching for fiction that appeals to you most, adapt it, apply it to your fiction, and stay true to the story that you’re trying to tell. Class dismissed!

Shaun van Rensburg

Shaun van Rensburg lives in South Africa with his cat. Over the years, he has published several short stories in various anthologies. Most recently, his first novel was published through his imprint, Pink Dove Books.

info@pinkdovebooks.com