How to Give Editing Feedback That Writers Actually Appreciate

Today is a bit of a fun deviation, a blog about two sides of the same coin: giving editing feedback. Blue Leaf’s talented director, Michelle Meyer, will tackle the topic from an editor’s point of view. I can list her credentials and sing her praises (editor extraordinaire, wiz at Scrabble, makes the best savoury muffins), but she’ll probably just remove it all during edits because “it’s not relevant” (Agree to disagree) (M: It’s not! And we’ve played scrabble only once).

As for the writer’s side of things, that’ll fall to yours truly, Shaun van Rensburg. I’ve published a handful of short stories and, most recently, received the opportunity to share my two cents on various writing-related topics here at Blue Leaf Editing.

(M: That would be The Importance of Editing: A Writer’s Perspective and Short Story Fiction: Writing Powerful Stories in a Limited Space—highly recommended!)

Writer’s Perspective: The Write Way to Give Feedback

There are two periods in a writer’s life: Adolescence and adulthood. Much like when you’re a child and draw terrible pictures that adults fawn over, the adolescent stages need that same sense of praise from people.

There’s nothing wrong with praising a young writer, even if their work is terrible. You don’t need to lie, of course, but you can focus on positive writing feedback and what works in their stories—and even in the worst stories, there’s always something that works.

Eventually, though, all writers grow up. A lot of them want to make careers out of their writing. What does this mean in terms of feedback? They must be able to fix their mistakes to improve their writing.

They also need to develop some tough skin. In my opinion, it’s best if they start seeing their manuscripts as products—a clinical way to look at it, I know, but that’s what manuscripts and stories are at the end of the day.

Reviewers tend to be brutally honest because they pay for that right. In contrast, not all readers are writers. They don’t know how complex and chaotic the writing process can be.

Tips on Receiving Feedback

I was very fortunate to know Michelle when I started sharing my work with people. It was the first time anyone outside my family had read it. Honestly, the fact that someone was willing to read the drivel I wrote back then—let alone give me constructive criticism—meant the world.

The editor-writer relationship I’ve built with her has taught me a lot, both about giving and receiving feedback. I think the latter often gets overlooked when talking about feedback, which is why I’d like to share some tips for writers:

Don’t Take Offence

I get it. I’ve been there. I’ve seen others go through it. You have to remember, though, not to take criticism personally. People will have all sorts of reactions to your work. You don’t have to be happy about it, but—in my experience—there’s usually a reason why readers react a certain way to stories.

Listen to Your Editor

The more I work with editors, the more I realise just how invaluable they are. The best ones, like Michelle, can understand what a writer is trying to do while still editing with the audience in mind. Their changes are (more often than not) beneficial to the story.

Don’t Share First Drafts

They’re usually terrible, even if you don’t think they are. It’s better to get feedback when the story has been polished. Let first drafts rest, return to them with new eyes, and then improve them. It won’t be fair to either you or a reader if your work doesn’t showcase your best.

Practical Tips for Giving Effective Feedback

Now that that’s out of the way, there are a few tips that I can share for providing helpful criticism to writers. In my experience, the best feedback is honest, firm, clear, and professional.

Take note: Being honest is not the same thing as being rude.

Too many people are afraid that they’ll offend writers by giving honest feedback, but I like to remind them that everything is fixable before it goes to print. Once it’s out there, it’s there for the world to see—mistakes and all. That’s not ideal. Here’s what you should keep in mind to help writers prevent that:

Your Emotional Reaction Matters

Sometimes, you may encounter something that makes you hesitate: a character, a plot point, dialogue, or even the story itself. Let the writer know. Better yet, let them know when you feel anything. If a character makes a choice you think they wouldn’t have, if a particular paragraph pulls you out of the story, or if some world-building aspect feels anachronistic, make note of it. A lot of what makes a good story depends on a reader’s emotional reaction to it.

Vagueness is Ineffective

Often, feedback is vague because readers don’t want to say what they’re really thinking in case they offend the writer. As I said before, honesty doesn’t have to be rude, but writers can’t improve if they don’t know what they’re doing wrong. Have you ever seen a terrible singer audition for American Idol and wondered why no one told them they couldn’t carry a note?

Dishonesty is the worst thing you can do for a writer who wants to write for a living.

Comment On What You Like and What You Don’t

This isn’t always possible, mind you—especially when you’re on editing deadlines—but it creates a sense of balance for the writer. A single line of encouragement here and there goes a long way.

Your Bias May Be Beneficial

If your go-to genre is high fantasy, but the story you need to give feedback on is a whodunnit, your feedback may be biased toward your reading preferences. Gravitating toward what you know is only human. Once you realise this, nothing is stopping you from using your reading preferences to your advantage.

For example, I’ve found that fantasy readers have a knack for knowing when the plot dips, romance readers are usually great at sensing tension (of all kinds) between characters, and mystery readers tend to pick up on effective and ineffective foreshadowing.

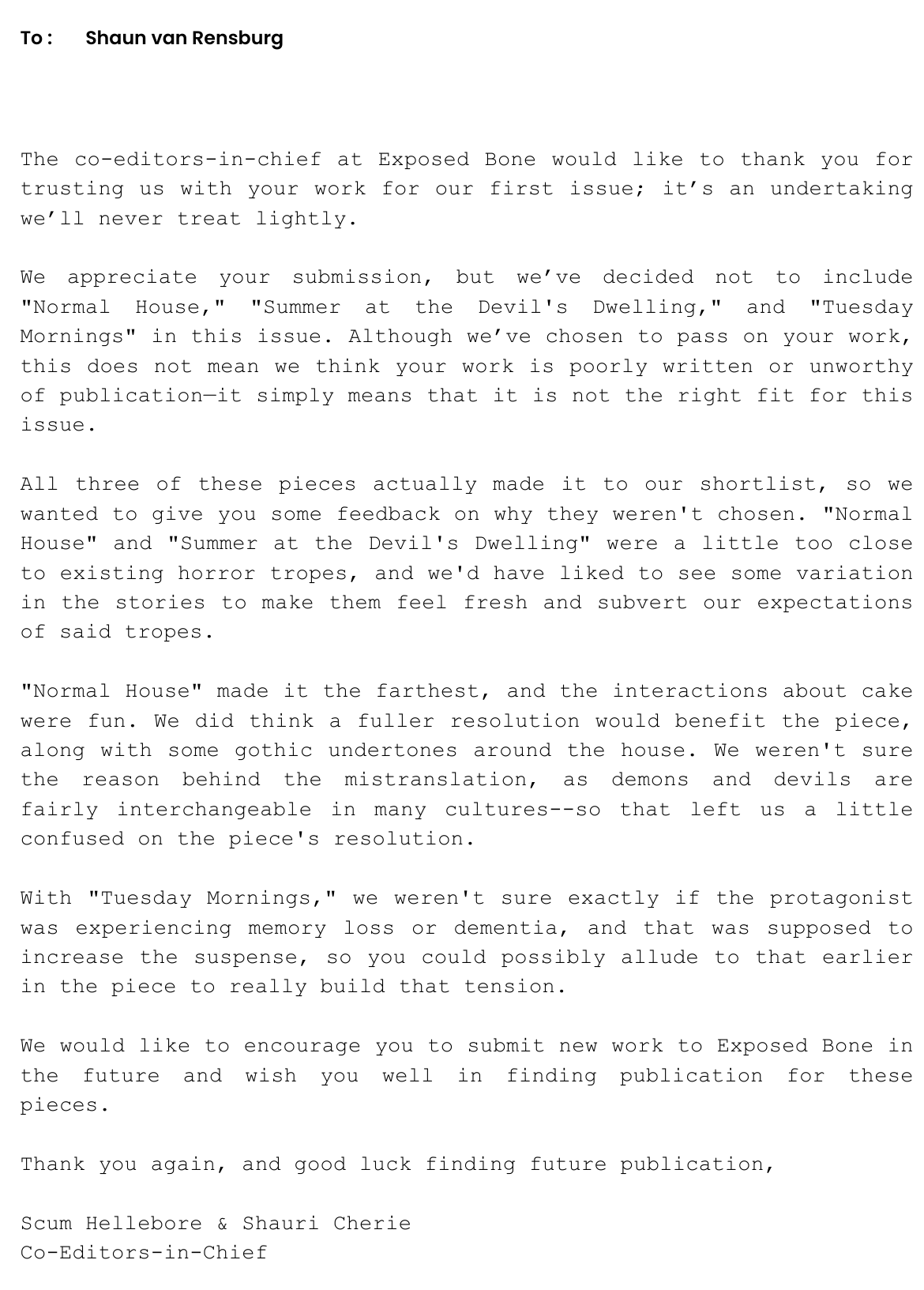

An Example of Effective Feedback

As an example, here’s the rejection email for a few stories that I submitted to Exposed Bone:

This is how you should give feedback on style and content. It’s what I consider constructive criticism. Their feedback wasn’t vague. They were firm in what didn’t work for them, gave honest editing tips on what they thought would improve the stories, and all with respect and professionalism. This is the type of feedback I can use to improve my writing.

Editor’s Perspective: Tales from the Feedback Trenches

“Communication is key”.

You’ve probably heard this from multiple advisors, counsellors, self-help books, friends, and family—to the point where it’s gotten generic and boring. But bear with me one more time, because it’s still the truth: communication is key. Wait, let’s improve on that: effective communication is key.

So, as an editor, how do you effectively communicate feedback to a writer?

Stick to the Point

Your editing feedback shouldn’t compete with the content you’re editing, and the writer definitely doesn’t need a lead-up. Instead, feedback must be clear and concise. If you give too much, it might become overwhelming.

At university, one of my lecturers always criticised me about how I formulated author queries in editing assignments. Apparently, I was too rude. The “right” way is to be as polite and long-winded as possible: “Would you please mind fixing [X]?”, “Would you please add [X] to make these elements agree and bring cohesion to the paragraph?”

Uhm, no.

I didn’t agree then and I still don’t agree now. As an editor, that’s wasting words and you know better. Simply requesting “Please add a reference” is fine.

The P-word Here is Professional

The writer hired you for a professional service, so you need to act professionally. Nothing personal or petty. For example:

Don’t: This isn’t right at all. I think you need to step up and do better. Where have you been published before? This story idea is weird, I don’t think people will like it.

Do: What a unique story idea! Keep your target audience in mind, so your story really resonates with them. Consider beta-readers for direct feedback.

The goal is to elevate writing, not point out flaws. Especially when it comes to creative work. As an editor, you must understand that putting out a piece of creative writing is personal for the writer. Actually, it’s downright scary. It’s a little bit of themselves that they willingly give over for criticism, bracing for the worst.

I’ve found that academic writers are more receptive to feedback, possibly because editing is just part of the academic publishing process, like peer review or getting the ethics committee to sign off. In fact, I’ve worked with some academics who rely too much on the editor and just think: “The editor can fix that”. (Too) many inconsistencies, incomplete references…it was bordering on lazy. BUT professionalism still prevailed.

Give Positive Feedback Too

Feedback doesn’t always have to be negative. Adding positive comments to a document is one of my absolute favourite things to do during the editing process (right, Shaun?) (S: It’s true ^-^ I’m ever grateful). As an avid reader myself, I can’t help but get excited by plot twists, smart descriptions, or excellent dialogue.

Take a scroll through the below screenshots of positive feedback examples. It doesn’t have to be long or soppy—just a nod of encouragement.

Small encouragements dotted throughout the text go a long way, keeping the writer from drowning in the proverbial red sea.

Don’t Impose Your Preferences

While language has definite rights and wrongs, many editing decisions also come down to style preferences. This means it’s a matter of consistency, hence, universities, publishing houses, and businesses have style guides to help you implement and maintain the relevant preferences.

However, there’s another, just as important thing you need to maintain: the writer’s voice. That unique way that makes readers say, “Classic [X]. He/she has the best way of phrasing it.”

So, it’s a very delicate thing, a real balancing act to enforce correctness but maintain the writer’s voice. It’s tempting for editors, especially when green, to go in guns blazing and fix all the “errors” they see. But you must learn restraint. Often, the error is actually you disagreeing with the writer’s preference, meaning you’re chipping away at their voice if you change it.

Give Examples

Ironically, you and the writer might not be speaking the same language. You think your editing feedback makes complete sense, but all the writer sees are question marks. That’s why examples are encouraged.

Consider this: you want to recommend a formatting change to the writer. Instead of painstakingly typing out how they should implement it (bold this, indent that, increase line spacing here), copy the relevant text into a blank doc, implement the changes, and show it to the writer for easy side-by-side comparison.

Personally, I like including examples in in-text and email feedback. In-text is great for very specific examples that are only relevant to that section, paragraph, sentence, while email is perfect for longer, bigger-picture feedback—and attachments!

I recently discussed how to approach a steamy scene between a recently married couple with a writer. And no, no picture examples were involved. The scene had to fit the genre, so subtle and suggestive, nothing graphic. I sent the writer examples from other books to help.

It all comes down to this: Your editing feedback should help the writer elevate their work because you have the same goal—effectively communicating information. By respecting each other as professionals and communicating well between yourselves, you’ll reach that goal swiftly and with no small amount of satisfaction.

Key Editing Feedback Takeaways

- Your feedback should be clear, concise, professional, and honest.

- Offer specific examples to clarify feedback and help writers implement suggested changes effectively.

- Praise is essential, especially for young or inexperienced writers. By providing positive comments alongside constructive criticism, you can encourage writers and help them maintain their motivation.

- Writers should still develop tough skin and view their manuscripts objectively. This means listening to an editor’s insights.

-

- In turn, editors must respect writers’ unique style and voice while correcting errors.

Collaborate, Don’t Cry: Make the Red Pen Work for You

And that’s a wrap, folks. But a few words before we go: Writing is a collaborative process. When you realise that honest and professional feedback assists in making the work better and that the editor isn’t usually out to get you (I say ‘usually’ because they might be a vampire, so you never know) (M: I can testify to that), the process of improving gets much smoother.

I know Michelle shared this Stephen King quote previously, but it’s just too true: “To write is human, to edit is divine.” If you’re not convinced by that just yet, you can explore the inner workings of a writer’s mind by reading Diana Gabaldon’s excellent post, Want to Watch Me Write? or by taking a closer look at a copy edit pass over on Gail Carriger’s blog.

You’ll see what I mean when I say it’s a collaborative process—and hopefully, it’ll help you provide more effective feedback in the future.

FAQs

For writers

Don’t let editing feedback scare you! Read through the suggestions, see what keeps popping up, and decide which ones to tackle first. Think about each comment, make changes you like, and ask questions if anything’s unclear. The more feedback rounds you go through, the smoother your writing will become.

Don’t hesitate to ask for clarification. Ask the editor for examples or further explanations to ensure you understand their perspective and how it applies to your writing.

It’s important to approach feedback with an open mind. Consider the editor’s perspective and evaluate whether their suggestions could enhance your writing. You don’t have to implement every suggestion, but being receptive to feedback can help you grow as a writer.

Remember, editing feedback is about your writing, not you as a person. It’s an opportunity to learn and grow, not a reflection of your worth. To build resilience, seek feedback from diverse sources with different perspectives. Focus on the actionable advice you can use to improve, and celebrate every step forward.

A little prep goes a long way! Polish your work as much as possible before hitting submit. Proofread for typos and grammatical errors, ensuring it’s well-formatted and easy to read. Having clear goals for your writing and specific questions for the editor will help them give you the most targeted feedback.

Editors thrive on collaboration! They admire writers who communicate openly, ask clarifying questions, and are responsive to feedback. A willingness to revise and improve your work goes a long way, along with respecting their expertise and experience. Remember, you’re both on the same team: crafting the best possible piece of writing.

For editors

Not all feedback is created equal. Helpful feedback should be specific and actionable, focusing on improving the work itself, not personal attacks on the writer. It should offer straightforward suggestions they can actually implement.

Conversely, unhelpful feedback is often vague, judgmental, or fixated on the writer’s personal qualities instead of their writing. Ensure your comments help the writer understand what’s working and what needs work without unnecessary negativity.

Start by acknowledging their concerns and asking for their perspective. Focus on specific suggestions with clear reasoning, ensuring they understand how the changes benefit the work. Offer options and compromises, and remind them that your goal is to elevate their writing together. If all else fails, professionally call it quits.

Writing communities, online courses, YouTube videos, and various books can help you get behind the nitty-gritty of giving feedback. For example:

- Our Sharpening Your Editing Skills blog has a downloadable editing resources list

-

- HBR’s Giving and Getting Feedback article series. While focused on employer-employee dynamics, you can apply the core ideas to editor-writer relationships.

-

- Eventbrite hosts numerous webinars. Register to join discussions about editing feedback and multiple other topics.

-

- Bestsellers like The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People (particularly Habits 4 & 5) and How to Win Friends and Influence People discuss essential people skills you can use to enhance your feedback.

Don’t generalise or leave comments that can be ambiguous in any way. Instead, pinpoint specific areas for improvement and suggest concrete solutions. Use concise language and clear examples to illustrate your points.

Like all good things, developing a keen eye comes with practice and time. Style guides, especially from academic presses, take preference because the writer agreed to submit a manuscript in accordance with the style guide to get published.

However, we still recommend pointing out to the writer when you make stylistic changes that influence their voice. This gives them a clear reason for the change, instead of leaving them in the dark, assuming the worst.

Michelle Meyer

Michelle Meyer is the director and head editor of Blue Leaf Editing. With a background in publishing, bookselling, and marketing, she aims to turn all the content she edits into its best version. In her spare time, Michelle reads and watches as many horror and fantasy content as she can.

Shaun van Rensburg

Shaun van Rensburg lives in South Africa with his cat. Over the years, he has published several short stories in various anthologies. Most recently, his first novel was published through his imprint, Pink Dove Books.

info@pinkdovebooks.com