Hooked From the Start: Editing Tips for Strong Opening Lines (and Closing) in Fiction

While you shouldn’t judge a book by its cover, no one ever said you shouldn’t judge it by its first line. The stronger they are, the harder they are to forget. Case in point: “It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife.”

A lot can be said about how a book opens and closes. Strong opening lines should hook the reader and make them want more, and strong closing lines should satisfy the reader.

That’s why we’re taking a look at both opening and closing lines. They have a symbiotic relationship. The best ones are connected by threads, making the reader want to turn back to chapter one as soon as the story is finished.

Table of Contents

What are Opening Lines in Fiction?

Opening lines in fiction are the first sentences that greet the reader and act as a gateway to the story. A great opening line grabs your attention, sets the tone for the story that’s about to unfold, invites you in, and keeps you hooked. Just like first impressions matter in real life, opening lines hold immense power, making them a tricky part of fiction editing.

How to Develop Strong Opening Lines

Now, like everything related to writing and editing, there’s no inherent “right way” to develop opening lines. Your favourite opening lines are probably not the same as someone else’s, just like your taste in books. There are many ways to approach it, based on genre, theme, or personal preference. We’ll discuss some of the common methods here.

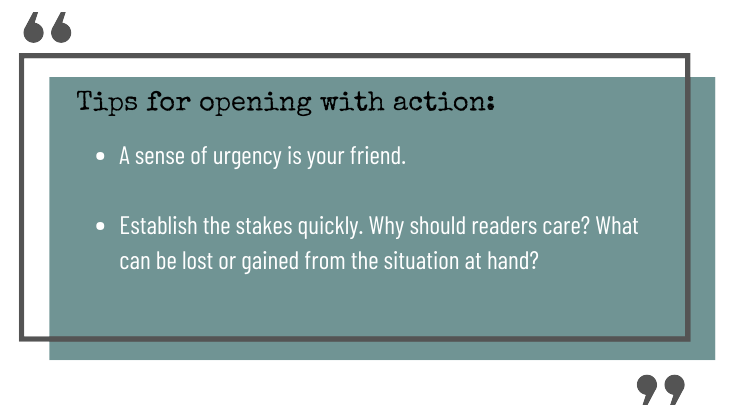

Action!

It doesn’t need to be action the way you’re probably thinking of—guns, car chases, life and death, and all that jazz—but dropping readers in an urgent situation that demands their attention can be a great way to write an opening line. Consider the opening for The Devil Wears Prada by Lauren Weisberger:

The light hadn't even officially turned green at the intersection of 17th and Broadway before an army of overconfident yellow cabs roared past the tiny deathtrap I was attempting to navigate around the city streets.

We don’t know the character yet, but we know the feeling of being stuck in traffic with places to go. It’s urgent, immediate, and relatable. It makes us want to read further: Why is the character driving? Where is the character driving? Will they make it in the “tiny deathtrap”? It’s not a catchy opening line—action lines usually tend to sacrifice this for the sake of creating tension quickly—but it does what it’s supposed to and hooks the reader off the bat.

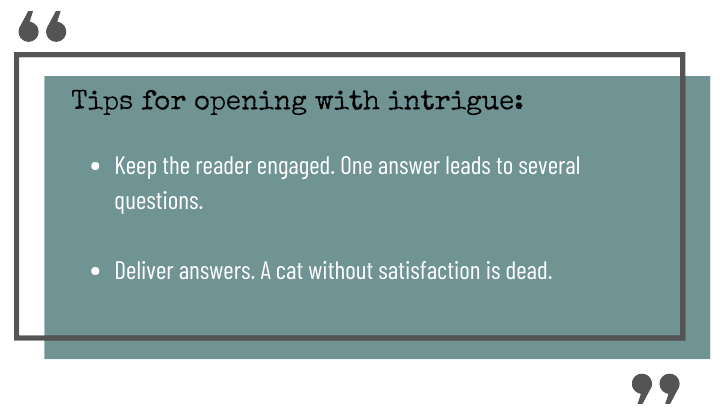

Does Anybody Have Any Questions?

Curiosity killed the cat, but satisfaction brought it back. One way to write an opening line is to make sure it intrigues readers enough so that they move forward with the story. A good example of this can be taken from The Magicians by Lev Grossman:

Quentin did a magic trick. Nobody noticed.

It works because the reader’s first response is: “Wait, why didn’t anybody notice the magic trick? And what type of trick was it that would go unnoticed?” These questions are all answered in the first paragraph—but the chapter is so well constructed that by the time you have the answer, you’re already hooked and have more questions that need answering.

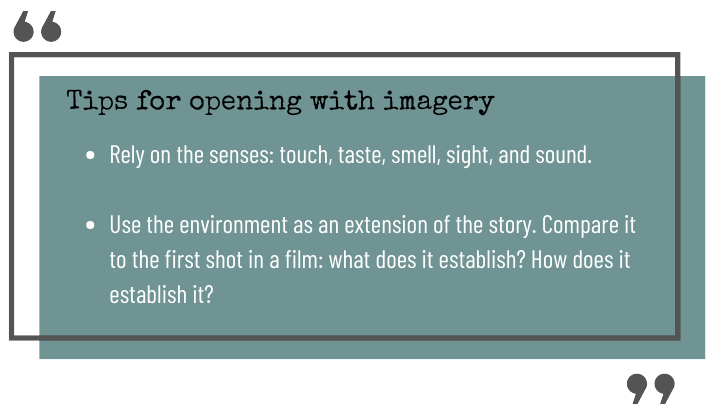

Real Enough to Touch

A descriptive opening sets the scene by using imagery to hook the reader. Similar to starting a novel with action, this method takes a bit of extra work to write an opening line that’ll stick in the mind easily. It’s effective, though, because it sets the imagination to light. A novel that does this remarkably well is The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde:

The studio was filled with the rich odour of roses, and when the light summer wind stirred amidst the trees of the garden, there came through the open door the heavy scent of the lilac, or the more delicate perfume of the pink-flowering thorn.

Do you see why it works as an opening line? It grabs the reader by invoking their senses: the scent of the flowers, the feel of the breeze. Wilde didn’t even have to establish the room beyond mentioning the door. We can already guess its location by the gentle scene he sets. It’s cosy and calm, belonging to someone who can afford to buy and care for flowers.

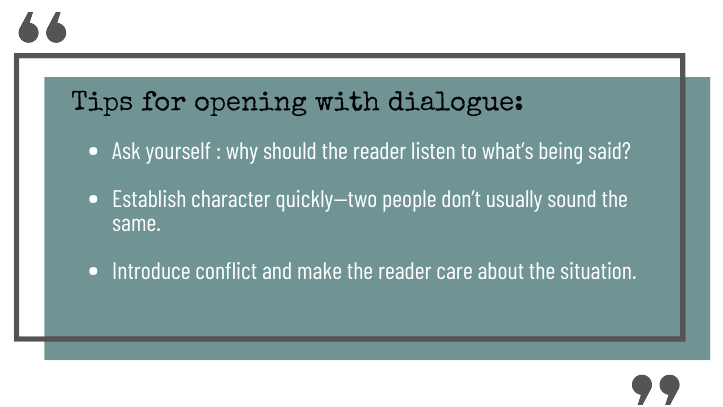

Dialogue That Speaks

Jumping into dialogue for the opening line is another great option. It’s uncommon, though, because it’s difficult to set the scene when you begin a story with character dialogue. That’s why it’s important to make sure that whatever’s being said is worth it. Here’s an example from Jennifer L. Armentrout’s From Blood and Ash:

“They found Finley this eve, just outside the Blood Forest, dead.”

It’s catchy, piques curiosity (why did Finley die?), and alludes to the genre (the Blood Forest). The reader wants to know more—who’s speaking? Why’s the news important?—and that’s the sign of a good opening.

If you’re thinking of opening with a conversation, that’s also possible. It has the advantage of creating tension rather quickly. Here’s an example from Venetia by Georgette Heyer:

“A fox got in amongst the hens last night, and ravished our best layer,” remarked Miss Lanyon. “A great-grandmother, too! You’d think he would be ashamed!” Receiving no answer, she continued, in an altered voice: “Indeed, you would! It is a great deal too bad. What is to be done?”

See what Heyer is doing? She sets the scene (domestic, country) and introduces conflict into the conversation by having one character unresponsive (no one likes to be ignored). Admittedly, it’s not as effective as Armentrout’s, but each opening fits readily into its respective genres.

What are Closing Lines in Fiction?

Closing lines in fiction is your story’s last impression on the reader. A good closing line is just as important as a good opening line. It’s the icing on the cake, that last cookie in the jar, the leftover crumbs in a packet.

Pull it off, and your readers will be more than willing to flip back to the beginning and read the first line again. Get it right, and you’ll leave them smiling (or crying—whichever have you).

How to Develop Strong Closing Lines

We’ve said it before, and we’ll say it again: writing is unique. Developing closing lines depends on you and your story. Of course, there are editing best practices that you can follow to assist you, but none of this is set in stone.

You’ll need to do whatever’s right for your project. An ending that leaves room for interpretation? Go for it. An ending that shuts all doors and ties all strings? You do that.

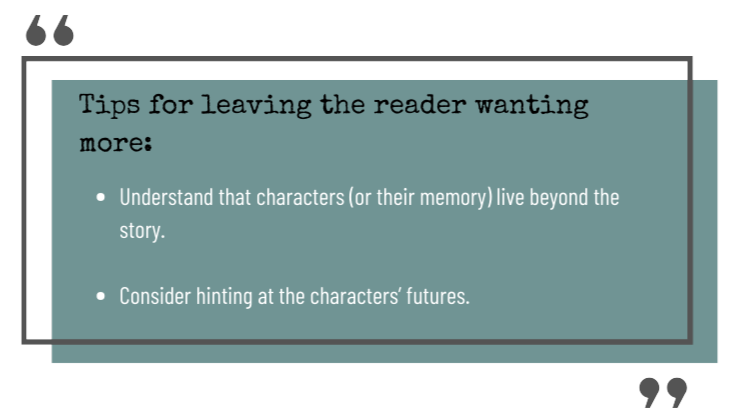

Encore!

You and your readers want the closing line to be so good that they want to gather to reread the book or rush to buy the next one. You want to leave them satisfied with what they’ve just read—remember, they’re saying goodbye to characters they’ve spent a lot of time with. Here’s an example from Rick Riordan’s Percy Jackson and the Lightning Thief:

“I’ll be back next summer,” I promised him. “I’ll survive until then. After all, I am your son.” I asked Argus to take me down to cabin three, so I could pack my bags for home.

The closing line promises more to come—if not for the reader, then for the protagonist. It also ties back to the beginning, but with the character having grown significantly. It’s a good closing line because it leaves readers thinking about what comes next.

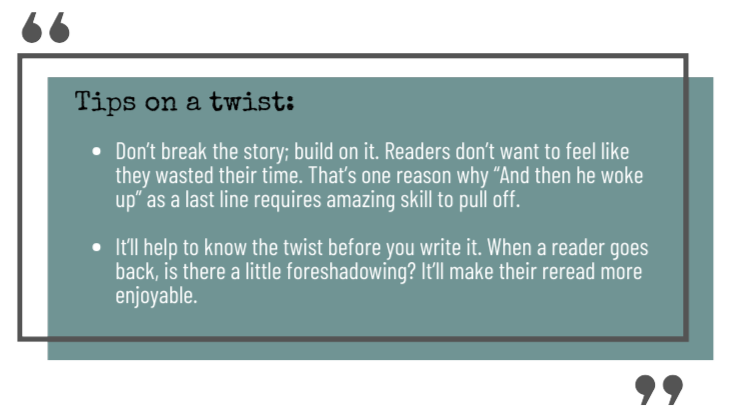

I Did NOT See That Coming

The disbelief, the surprise, the downright twist. There’s something to be said for a closing line with an impactful revelation—a line that changes the story’s meaning in one fell swoop.

A strong closing line that makes the reader think: I need to read this again. One of the most famous examples would be from Shirley Jackson’s short story, The Lottery, which ends with:

“It isn’t fair, it isn’t right,” Mrs. Hutchinson screamed, and then they were upon her.

Why does it work? Because no one saw it coming. Jackson subtly builds the tension, but then pulls the rug right out from under our feet. She even said that many of her readers were convinced, right up until the end, that the prize would be a washing machine.

Here’s another example of closing with a twist, taken from Stephen King’s The Boogeyman:

“So nice,” the boogeyman said as it shambled out. It still held its Dr Harper mask in one rotted, spade-claw hand.

The revelation of the psychiatrist’s identity makes readers do a double take. Knowing what they know now, can they identify the signs on a reread? Maybe they should read it again, just to be sure.

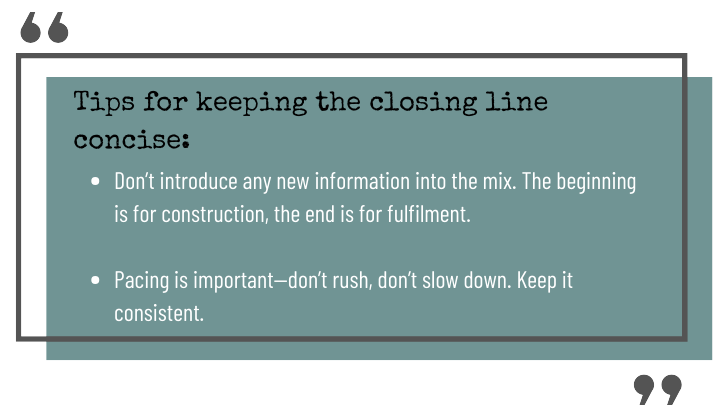

Make It Snappy

Now, let’s make one thing clear: your closing line doesn’t need to be short. It needs to be concise, coherent, and contribute to the plot (yes, even if it’s the last line). Readers know the end is coming and, even if they might not want it to arrive, dragging it out is never the answer. Let’s look at the closing line from Gone with the Wind by Margaret Mitchell:

After all, tomorrow is another day.

It’s to the point, making it work on multiple levels. Doesn’t reading it bring you a sense of hope? In the story’s context, it does remarkably well as the book’s closing line (and it’s a big book, so a lot was riding on it).

Mixed Feelings

You’ve done it—you’ve journeyed with the characters to the end. You’ve spent so much time with them, rooted for them, and cried over them. The ending needs to stay true to this experience.

The closing line needs to be aware that it’s not only the end of the book, but the end of a reader’s journey with the characters. Let’s take a look at the last line from J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows:

The scar had not pained Harry for nineteen years. All was well.

It’s impactful, returning readers to the story’s beginning (not the book, mind you, but the story), and it’s concise while concluding the plot. It works well as a closing line because it’s satisfying and resonates emotionally with readers.

Back to the Beginning

We’ve already mentioned this, but connecting your end to your beginning—your closing line to your opening line—is one of the best ways to create a sense of satisfaction.

If done right, it leaves readers with a sense of resolution and closure (careful, though, because if done wrong, it can seem contrived and unsatisfying). One of the best examples is from The Haunting of Hill House by Shirley Jackson. Here’s the opening:

No live organism can continue for long to exist sanely under conditions of absolute reality; even larks and katydids are supposed, by some, to dream. Hill House, not sane, stood by itself against its hills, holding darkness within; it had stood so for eighty years and might stand for eighty more. Within, walls continued upright, bricks met neatly, floors were firm, and doors were sensibly shut; silence lay steadily against the wood and stone of Hill House, and whatever walked there, walked alone.

Here’s the closing:

Hill House itself, not sane, stood against its hills, holding darkness within; it had stood so for eighty years and might stand for eighty more. Within, its walls continued upright, bricks met neatly, floors were firm, and doors were sensibly shut; silence lay steadily against the wood and stone of Hill House, and whatever walked there, walked alone.

The end mirrors the beginning and this works well as a resolution—especially in the story’s context (if you’ve read it). It doesn’t feel forced and readers don’t feel cheated by the reused words. They’ve come full circle and they know it. Better yet, the words have taken on new meaning by the time the readers reach the end. Jackson was well aware that, though the words were identical in some instances, they wouldn’t be read that way.

Editing Tips for the Best Opening and Closing Lines

Reviewing and Revising Opening Lines for Maximum Impact

A strong opening line has one purpose above all else: to hook the reader. Whether that’s by piquing curiosity, sparking imagination, or dropping a reader right into the middle of the conflict. To ensure you produce an impactful opening line, ask yourself:

- How effective is your hook? Would it compel readers to move forward?

-

- Have you experimented with different types of opening lines to ensure you’re writing the strongest opening line possible for your story?

-

- Is there a sense of symmetry between the opening and closing lines?

Refining Closing Lines to Resonate with Readers

Strong closing lines are more difficult to perfect than strong opening lines. Closing lines have to work with what’s already been established. When editing your closing lines, ask yourself:

- How effectively does your closing line signal finality?

-

- Is there a sense of symmetry between the opening and closing lines?

-

- Does your closing line stay relevant and true to what’s been established regarding character, plot, and theme?

-

- How much of an emotional impact does it have on the reader?

Hook, Line, and Sinker

Judging a book by its opening line is a valid way to estimate if you’ll enjoy it or not. That’s why a strong opening line needs to hook the reader and carry them through the first chapter. Hopefully, they’ll be in it for the long haul by then.

A strong closing line, on the other hand, needs to be symmetrical with the opening line. This will help readers feel a sense of resolution. The best closing lines leave a lasting impression on the reader.

The better they are, the more likely a reader will pop back for more. At any rate, people often say it’s not how you start, but how you end. In the case of a story, strong opening lines and strong closing lines are, without a doubt, mutually beneficial.

Blue Leaf Team

The Blue Leaf Editing team has over 10 years of combined editing, publishing, and book industry experience. We’re passionate about content and storytelling, and sharing our knowledge with others.

info@blueleafediting.com